I don’t pretend to be anything other than an

average amateur turner. I love my turning, but I have never felt

the need to develop my skills to a point when I didn’t need

my multi-faceted turning tool (ie abrasive!). I can turn a bead

with a skew in the privacy of my own workshop, but cannot make a

series of beads the same size along a piece of wood without a

beading tool. There, I’ve admitted to all and sundry that I

cheat!

I try to turn work that I enjoy and that I would like to keep.

There is nothing special about my traditional turning, but I have

found a couple of useful tips along the way as a result of

numerous disasters and here they are, if you are interested.

Making sure there is no bump in the bottom of a bowl or

platter.

I make a lot of very thin bowls / platters in dry timber. The

technique for getting thin walls is the same as you would use on

wet wood – you do a small section right down to the

thickness you want and then do the next one. You never try to go

back or you will get chatter (or shatter!!!).

As you progress down the sides of the bowl, you need to keep a

hefty amount of wood in the centre over the chuck to give you

stability and stop the work from flexing and changing shape.

The reason I use dry wood is so that the final shape will be

stable and will not warp enough to notice visibly.

There is a temptation to remove the centre when you get to it and

carry on making the curve from where you have got down the

side.

As I worked towards the centre of a piece I noticed I would be

twisting – but the centre of the twist was not the centre

of the bowl – thus leaving a bump in the centre.

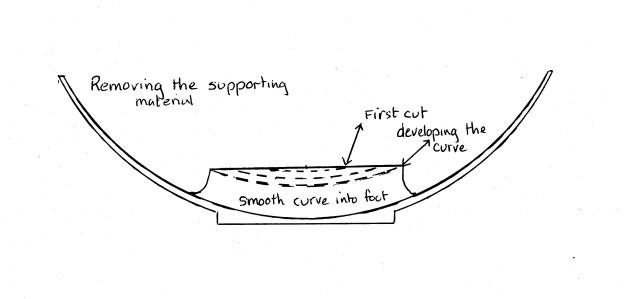

I found that if I took off the waste support material flat (ie

parallel to the rest) and then started to generate the curve from

the centre of this flat area, gradually moving the cut further

out, I got a much better curve, and when I reached the edge of

the flat, I would have one final cut, the same thickness all the

way that blended the 2 curves together.

Perhaps a picture will help:

It is a bit exaggerated - the step that you end up with is

generally about 1mm - but it seems to work - and sinking the

curve into the foot seems to help make the curve a really

satisfying shape!

Torn grain near the foot of a bowl

I like to raise my bowls up from the surface they are sitting on and never use a recess to chuck the piece. On a thin bowl a recess would soon become a hole and instead of a bowl you would have a lamp shade. I try to cut rather than scrape wood and usually get a reasonable

finish from the deep fluted bowl gouges that I use (Henry Taylor

super-flute – basic 45 degree angle – straight grind. I

rarely use a swept-back grind).

However carefully you cut and however sharp the tool, the 5mm

next to the foot is often very difficult to turn without a little

torn grain being visible. A pull cut gets close to the spigot but can tear the grain. A pushing cut from the edge to the middle also tends to tear the grain. You want to cut from the middle outwards to get the cleanest result, but you cannot get to the 5mm or so closest to the spigot.

There are all kinds of scraping tools that can be used to save

the day – my preference is to shear scrape with a Gary

Rance round bar skew chisel with a burr pushed onto the cutting edge with a diamond file (they come in several sizes – I

mainly use the ¼ inch and the ½ inch and aim to

sharpen them straight across with the grinder set up to 30

degrees). The burr is easily removed when you want to use the

tool as a standard skew chisel and I prefer the straight across

grind (without a long point) – it is very versatile.

You really want to cut the wood rather than scrape if possible,

so the old cabinet-makers trick of putting a burr on one side of

the tool by gently sharpening the other side with a diamond file

gives you delightful, tiny perfect shavings when you cut with the

tool at 45 degrees to the wood and the rest level with the middle

of the bowl. It has to be a very light cut – especially

when reverse turning the base of a really thin bowl or

platter!

Beads

As previously mentioned, I cheat! I have never had the

determination to do enough practice to be able to make a row of

identical beads on a piece. My beads have been most successful using Ashley

Isles beading tools – they come in a variety of widths and

do not break the bank!

They have a semi-circular flute which is nearly the same width as

the tool and the end is ground at about a 30 degree angle to form

a point that shows the profile of the bead. It is sharpened by

rubbing a diamond file over the sloping face.

You have the tool rest set at about the middle of the piece and

set the tool on the rest with the flute downwards. This is not intuitively the way you would present the tool, but it is the right way. You then

gently push the tool into the work. I have found that gently

rocking the end of the handle up and down can improve the cut.

If you push too hard until the whole profile of the tool is in

contact with the bead you are cutting, you are likely to pull

splinters of wood off the centre of the bead. Stopping just

before the centre touches the wood prevents this risk and gentle

sanding will complete the bead – or you can raise the

handle to drop the point of the tool below centre to complete the

cut as the centre starts to make contact.